Job market resources for faculty positions in communication

Table of Contents

I was thinking of sending some links to graduate students at my school, but realized the work of compiling these into a document probably meant I should share more widely. My experience on the job market was that there was simultaneously a lot but never enough information. What I’m sharing here is what I could track down from my bookmarks and so on from my job search 3 years ago.

I will add some commentary throughout, but let’s get this out of the way:

- I have been hired to a faculty position one time

- I have limited experience with being part of hiring committees

- It’s impossible to know what about my application is responsible for any of the positive results I had; luck is a big factor!

So bear in mind I do not share this as an expert, merely as someone who once wished for any and all information possible. Most of the external resources are not specific to my discipline of communication, so if you’ve wandered over to this post from another discipline it may still be somewhat helpful. That being said, I filtered out external resources that were obviously not (widely) applicable to my discipline.

Other disclaimers:

- These resources are generally assuming a US-focused job search.

- I applied primarily to jobs at so-called “R1” institutions and I tend to notice that a lot of advice from other resources makes similar assumptions. If applying to teaching-focused schools, try to look carefully for resources that call out how to tailor your application to them.

- My comments and many of the resources assume the reader is applying for their first tenure-track job. Some of this stuff will not cover the process of applying for another type of faculty job and/or applying for senior faculty positions.

If you find other good resources, please feel free to send them along. If you think something I’ve written or linked to is wrong, then definitely let me know.

Job ads

Note: This will be the most communication-specific part of this post.

Where to look

It goes without saying that you won’t be doing much applying if you don’t know of any openings. Communication is kind of “special” in that the field has at least three professional associations that tend to be considered very important by US institutions: National Communication Association (NCA), International Communication (ICA), and Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC).

Some departments/schools/colleges tend to value one or more of these above the others. There are also other associations for advertising, public relations, and all of the above at sub-national levels. As best as I can tell, only NCA and AEJMC really have enough job ads collected to be definite must-check sources (but see note about ICA later).

For my money, if the average communication PhD had to pick one place to look at ads, it’s NCA’s job page. There’s a high volume of ads although some are not faculty positions. Unless you believe you are unlikely to be interested in a job at any institution that would advertise with AEJMC, I’d suggest keeping track of AEJMC’s job ads as well. Yes, there will be lots of listings that appear at every single place you will look.

When I was on the market, ICA had a very simple jobs page that had roughly 10 ads. Now they have switched to the same underlying software as NCA. They clearly have many more ads than when I was on the market, but it is not clear to me how they compare to NCA and AEJMC. Nonetheless, if I was on the market today I’d still check the ICA jobs page regularly.

There are also a couple places that are not communication-specific that might be worth keeping an eye on. The Chronicle of Higher Ed has a specific category for communication faculty postings on its job site. In my experience, it finds a few relevant ads that do not appear on the sites for professional associations. If you think there may be some jobs outside the discipline you would be qualified, this is a good place to look for that as well. All of this is true of HigherEdJobs as well.

Keeping track of relevant ads

This is a very individual thing, so feel free to ignore my advice and come up with your own system. Somehow you will have to keep track of jobs you may want to apply for. My suggestion is to immediately create some sort of record for jobs that you might apply for so that you don’t have to keep going back to your preferred source of job listings and so that you don’t forget it when newer job postings appear.

My system was a spreadsheet. I kept track of the institution, the position title, the unit that was hiring (e.g., Department of Communication), the type of institution (e.g. R1 or SLAC), and other information about the job and application. If I could figure out the teaching load, I’d make a note of it. I’d also take special care to find out whether they wanted recommendations to be submitted at the time of application so I could warn my references when things would be coming due.

See below for a screenshot of the first few rows of my actual spreadsheet.

Feel free to shamelessly copy as needed. I may have come up with this scheme from seeing someone else’s spreadsheet; by now I honestly don’t remember. Some of these categories may not be relevant for you. For instance, a lot of jobs I was mostly qualified for desired professional experience in a mass communication profession so I added a column to make note of that. I also had a column to keep track of progress in the individual search. You can see that in many cases I never did hear anything but eventually made the assumption that I didn’t get it 😄.

I also had a color scheme for jobs that I had not yet applied to but would (no color), jobs I was unsure whether I would apply for (yellow), jobs I had submitted an application for (green), and jobs I decided against applying for (red). I don’t know whether it was the best system but it worked for me.

Omitted from the screenshot is a final column that contained a link to the job ad so I could check for any missing details and follow through with the application.

I also kept a “job search” folder on my computer where I stored that spreadsheet, drafts of various application documents, and copies of everything I submitted or planned to submit to each opening. You can get a glimpse of the simple organization scheme below:

Within the institution-specific folders, I just kept a copy of the job ad along with all materials I submitted there. See below for an example from my Florida application:

This particular application asked for a CV, cover letter, separate list of references, and a teaching document that combined a teaching statement with evaluations.

One of the nice things about having some form of organization like this is that when you tailor your documents to a specific job, you can use previous applications to similar positions/institutions as a starting point — just don’t leave any references to the wrong school!

Information about the faculty job market in communication

At the big picture level, I think the market for faculty positions in communication could be described as “pretty good relative to other social science and humanities disciplines.” That does not mean it’s a good market, just that it could most certainly be worse.

Your own chances on the market depend on lots of things: your area of specialization, your ability to relocate, the types of institutions you are willing to work for, your research record, your teaching record, your professional network, and much more. Even then, there’s always going to be a luck factor. There’s no data available that will tell you ahead of time whether you will get the kind of job you want.

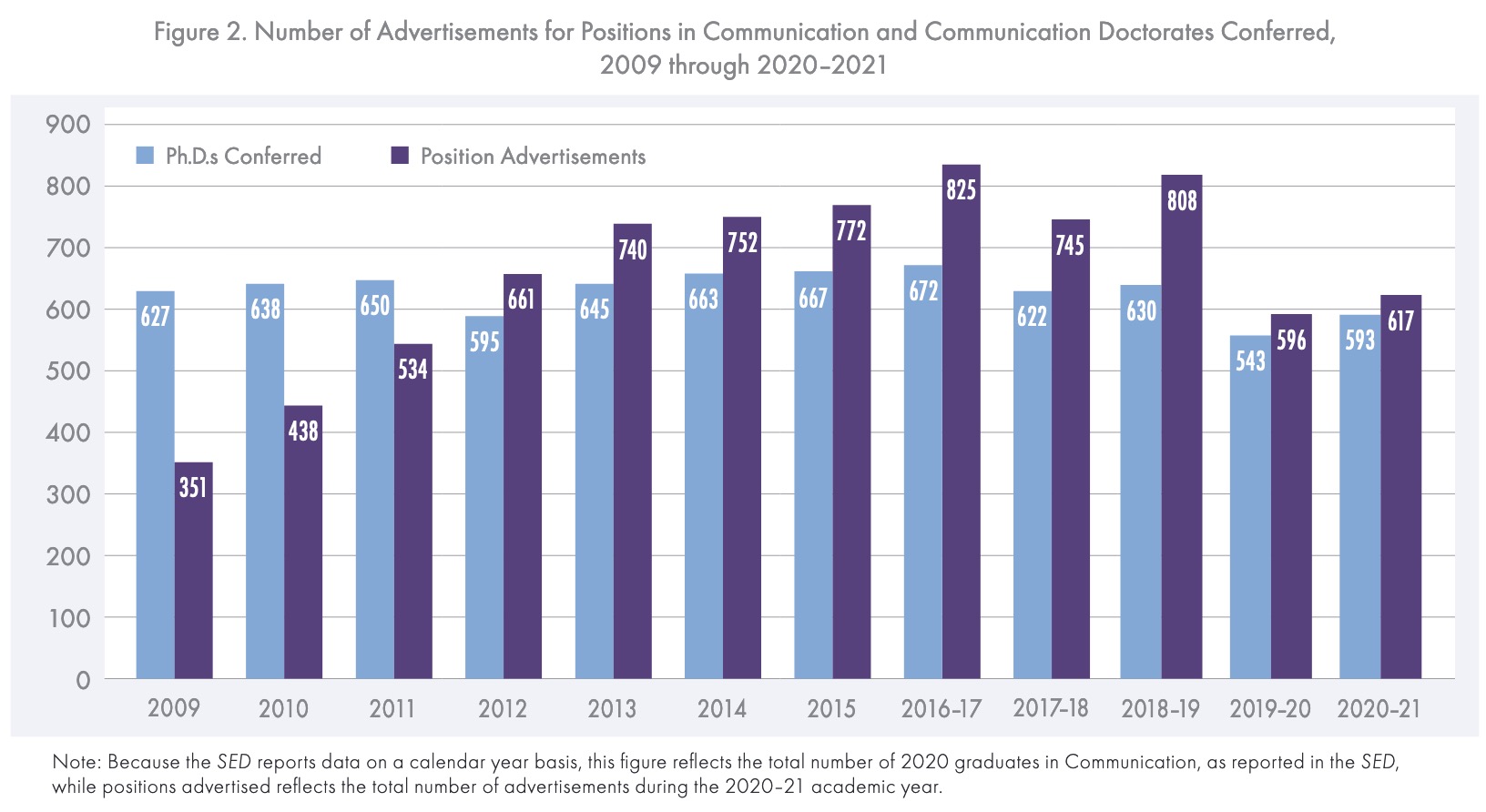

The simplest type of metric to assess the market conditions is to compare the number of open positions to how many PhDs are given each year. You would hope that for each PhD granted, there would be a faculty position available. This is of course very crude: not all PhDs want to be faculty, not all faculty positions are equally desirable, there can be a mismatch between the specializations of open positions and those of graduates, etc.

Each year, NCA publishes a report that counts the faculty job ads submitted to them as well as AEJMC. They then compare this with the number of communication PhDs granted by US institutions. As you might imagine, in addition to being crude this is very US-focused. There are some non-US job ads submitted to NCA and AEJMC job boards, but not many and most of them are from Canada.

Below is the key figure from NCA’s 2021 report:

You can see that the Great Recession had a brutal effect on the communication job market just like it did most sectors of the economy, causing the ratio of new PhD graduates to open positions to get close to 2:1. It eventually recovered to a level at which you had 808 open positions and 630 new graduates in 2018-19 before COVID reduced both the number of graduates and openings to an approximate 1:1 ratio.

As stated, this doesn’t mean everyone gets a job. First, you compete against people who graduated in previous years but have re-entered the market. Some positions, especially in the professionally-oriented parts of the discipline, do not require a PhD and instead may go to candidates with impressive professional credentials but not the PhD.

Only around half of academic postings are tenure-track, which many PhD graduates consider their main priority. Some are not faculty positions at all, which of course is just fine but may not be obvious at first glance. The number of tenure-track postings fell a great deal in the first post-COVID job cycle so time will tell whether it stays so low.

Additional complicating factors for thinking about these numbers include the fact that PhDs from other disciplines apply for and get communication jobs and people who received their PhDs from outside the US also apply for and get communication jobs. Of course, many who receive their PhDs in the US also work outside the country so it is difficult to say how it shakes out on balance.

For comparison’s sake, the ratio of new PhDs to job postings is close to 2:1 in history and English. Available data suggest communication is in a better position than some other related disciplines like political science and sociology as well. But as you can see from the preceding discussion, that doesn’t mean that things are good in absolute terms.

Application materials

The most useful information I can offer will concern the things you include in the application. This varies by posting, but there are several common documents you will need to have prepared in order to fully explore the job market.

One that I do not plan to discuss or share links about is the CV. If I get requests, I will consider it, but I find that most students have decent ones prepared and ultimately the style of this document isn’t as important as the underlying information. I trust that you won’t fail to mention your college education, your research, your teaching experience, your awards, and so on.

Cover letter

The cover letter is a rather important document, probably the most important thing after your actual accomplishments and qualifications as recorded on the CV. Happily, it’s the one with the most online help published about it. That being said, I still found myself wishing I could see more, more, more.

Resources giving tips for writing the cover letter:

- jobs.ac.uk guide (PDF)

- UChicago guide (PDF)

- Inside Higher Ed advice column

- The Professor is In, “Why Your Cover Letter Sucks”

A note on The Professor is In: There are many blog posts on that site about writing cover letters and all other aspects of the job market. It is worth checking out. The creator, Karen Kelsky, has also published a book you might consider buying or borrowing that includes more detailed advice than what is available on her site.

The cover letter is really fairly personal because it concerns you and your qualifications. This is something you need to have looked at by your advisor and/or other faculty mentors. Expect several rounds of feedback. After all of that, you’ll need to tailor each cover letter to the specific position — I didn’t find myself making major changes for most postings, but it depends on how different the kinds of jobs you’re applying for are. If you will apply to both research- and teaching-focused positions, you will at minimum want a different letter for each of those. There may be other reasons for substantial tailoring as well, such as positions that value professional experience, certain specializations, etc.

In general, you want to show that you fit the position and that you are well-qualified, all without under-selling yourself or over-selling yourself. What you will often hear is that most students are overly fearful of being boastful; the best thing to do, once again, is to consult your mentors and let them read your letter to figure out whether you are coming off the right way.

My cover letter

And bear in mind once again that whether or not I did something may not be proof of whether it is good or bad. Maybe the jobs I didn’t get were because my cover letter was no good. Maybe the job I accepted was in spite of a bad cover letter. These things are difficult to know. Conversely, maybe I had a killer cover letter and other parts of my application were limiting factors.

Since I so desperately wanted to find examples of cover letters in my discipline, you can read the one I sent to my current employer in 2019: Jacob’s UofSC cover letter.

Briefly, my goals were:

- Communicate that my dissertation was highly likely to be finished on time

- Show that I was an active researcher in the area of mass communication for this broad-topic and research-focused ad

- Give some information about the dissertation topic

- Explain that I had substantial teaching experience and care about that part of the job (although you can tell from the space given to it that I judged this position to have a strong research focus)

I had no special connection UofSC; in fact, I’d never been in the state of South Carolina at any point in my life. If I did have some special connection, I’d have considered mentioning it. There was an institution I applied to where I mentioned that I grew up nearby and this helped spark some nice small-talk when I interviewed later.

Teaching statements and evaluations

Although cover letters are basically mandatory, the rest of the documents I’ll discuss are not always requested by search committees. I think the most common extra document is the teaching statement and/or evaluations. Sometimes you will see a request for “evidence of teaching effectiveness” which I usually take to be a request for evaluations but you can interpret it somewhat broadly.

Again in the interest of full disclosure I was not and still am not a teaching superstar although I did have the benefit of a decent amount of experience by the time I was on the market. Ultimately you need to show you have potential as a teacher; it seems many search committees are not expecting excellence straight away especially if you haven’t had much independent teaching experience.

Needless to say, it is helpful to actually have a teaching philosophy before you start writing the document meant to describe your teaching philosophy. I think you probably do even if you haven’t put it into words yet. Read up on pedagogy as well as you are able — bearing in mind that this doesn’t need to be some big dissertation-scale research project — so you can speak the right language about teaching.

The Drake Institute at Ohio State has excellent resources for putting together teaching-related documents, including several examples of teaching statements. Check out their resources here. Michigan’s Center for Research on Teaching and Learning has a ton of example teaching statements.

In general, pay careful attention to the instructions for teaching documents since you may be asked for any of the following:

- A statement about your teaching philosophy (check for length limits)

- A summary of your teaching evaluations

- Actual copies of teaching evaluations

- A narrative describing your experience teaching

- Example syllabi/assignments

A combination of these requests may be merged into one document in some cases. The common phrasing “evidence of teaching effectiveness” is, as best as I can tell, a request for a summary of your teaching evaluations and any other similar things. If you’ve gotten feedback from teaching experts on your campus, for instance, you could include that as well.

My teaching documents

Below I share the documents I submitted to UofSC in 2019. One is a teaching philosophy and the other is a portfolio, which includes a narrative of my experience, a summary of evaluations, and sample syllabi/assignments.

I’m rather proud of these documents not because I think they prove I’m a great teacher — as I said before, I don’t think I am just yet — but because they really are accurate representations of me. The statement reflects the truth of my beliefs then and now about teaching. I have been asked in the years since about my teaching statement and it’s easy to continue to talk about it because it just so happens to be true for me.

A final note here is that I was applying to social science research focused positions and many of them sought computationally-oriented scholars. I tried to subtly communicate that I am a computationally-inclined and social science-oriented person in these documents. You don’t have to produce graphics to summarize your teaching evaluations, for instance, but that’s just in character for me. You also don’t need a reference list for your teaching statement, but that’s the kind of thing I do.

Research statement

Here we have the cousin of the teaching statement. To be honest with you, I am unsure how important this document is for prospective communication faculty. Many positions don’t ask for it, so it obviously isn’t very important in those cases.

The advantage in the case of research is that you may already have publications and other kinds of research outputs to show what you do and where you’re going. Research-focused positions generally ask you to give a research talk as well, which can cover much of the same ground.

The research statement can help you to connect the dots between the various aspects of your research record. This can be especially helpful if an outside observer might look at your outputs and think you seem to be working on unrelated topics. Here you can make the argument that they are in fact connected in some way. If you have a history of grant funding and/or anticipate getting grant funds upon hire, talk about those plans here.

Useful links:

- Cornell Grad School guide

- Penn Career Services guide

- Raul Pacheco on research statements and your research trajectory

- UCSF’s research statement tips [PDF]

- Carleton’s research statement tips

- U Chicago’s research statement overview [PDF]

- U Washington’s research statement overview [PDF]

- Philosopher’s Cocoon blog: Common mistakes with research statements

Two example statements:

My research statement

My current employer didn’t request a research statement, so I’ll share my statement submitted to another institution where I could have worked. Yes, it did have a typo in the very first sentence. That tells you either how closely these things are read or how little committees care about minor typos.

Diversity statement

These documents are becoming more common as a part of the application package. This is another case where you should read instructions carefully since some places treat this as a philosophical sort of statement while others are asking for something more like a personal narrative of the things you have already done. You may also see different length limits.

There’s a decent amount of advice about this out there. Here are some links:

- Inside Higher Ed 2016 advice

- Insider Higher Ed 2018 advice

- U Nebraska advice on diversity statements

- Vanderbilt guide on writing diversity statements

- UCSD diversity statement information (includes links to examples)

- Chronicle of Higher Ed diversity statement advice (paywall)

A couple example statements:

Just as I said with teaching statements, it’s important to mean what you say in these documents. And some people will have very important personal experiences to bring to bear in these statements. I have many kinds of privilege, so my ability to express personal experiences relevant to inclusion and equity for marginalized students is limited (albeit not zero). As with most things, showing rather than telling is preferred. Talk about actions above philosophy — that doesn’t mean you can’t state your values, but connect your values to what you have done or will do when hired.

My diversity statement

My current employer did not request a diversity statement, so I will share one from an application to a place where I could have worked. Note that the title of this statement was changed to match what was requested by the job posting (i.e., it didn’t ask for a “diversity statement,” it asked for a “statement on contributions to the success of students from underrepresented backgrounds.”)

As I mentioned before, these statements will be expected to vary quite a bit from one person to another both because different people will have different beliefs but also because your background and future plans will differ. My statement was focused on teaching, but others will have research programs that are much more oriented towards diversity, equity, and inclusion. Some others will also have more service activities directed towards these goals.

Post-application items

I don’t have as much to share for these few things that come up after you’ve submitted the application, but I wanted to share nonetheless.

Job talk

For research-focused positions, part of the on-campus interview process will be the so-called “job talk.” The vaguely-named talk will be an overview of your research, typically around 45 minutes long with 15+ minutes for questions afterward. This is a very important part of the process for these kinds of jobs; your record is the most important thing, but this is your big chance to show off what you’ve done and make it clear that the best is yet to come.

It is more difficult to find good advice about this in part because advice can get very discipline-specific and there’s just nothing out there about communication. I don’t feel qualified to dispense much advice on this, but I will say that the typical candidate will talk about 2-4 projects, usually with at least one of them something that is in progress or unpublished so far. It is common but not required to give some background about yourself before diving into your work.

The best candidates can make clear connections between their projects and leave the impression that this is all building up to something: a program of research. What I have said here about the structure of the talk is probably not quite right for those doing book-length projects and/or critical-cultural research, so bear in mind my experience is almost solely with candidates who do (usually quantitative) social science research.

Compared to other social science and humanities disciplines, my impression is that communication scholars are quite nice to each other in these sessions. But the purpose of these talks is to demonstrate the quality of your research, so don’t be caught off guard if you face tough questions. I do not hear many stories about overwhelming criticism, rudeness, interruptions, and so on in communication the way I do in some of those other disciplines, though.

Below are some links to resources that are not designed for communication researchers but I felt had useful information anyway:

- Kieran Healy on making slides

- Jesse Shapiro’s notes on giving applied microeconomics job talks [PDF]

- Chronicle of Higher Ed advice for STEM job talks

- Arthur Spirling’s slides on giving job talks in political science

Negotiation

I really don’t have the experience to give you authoritative advice about how to negotiate, but I’ll share some links and some factual information about the process. It may not be surprising to hear that tenure-track offers in the US are usually negotiable at least along some parameters. Note that negotiations for non-tenure track positions are not necessarily expected and you really need to talk to someone familiar with the specifics of your situation before trying to negotiate in those cases. My comments will focus on tenure-track positions in the US.

The things that you may negotiate include:

- Base salary

- Summer pay (a.k.a. “ninths”)

- Teaching releases and/or teaching load

- Startup research funds

- Technology budget (if not part of startup)

- Moving budget (if not part of startup)

- Research/teaching assistants (if not part of startup)

- Conference/travel funding (if not part of startup or given to all faculty by department policy)

- Paid visit to look for housing before your appointment begins

- Spousal hires

- Aspects of tenure — time until tenure or being granted tenure upon hire (only relevant to those who have already pre-tenure experience)

- Timing/frequency of sabbatical

Generally speaking, don’t expect to negotiate all of these things at once. Presumably the offer you receive will be just fine for some of these categories. As you will often hear, it is important to get the best base salary you can because all your future pay raises are affected by that number. Then again, your future employer also knows this and may have hard constraints from superiors for how much they can offer.

For public universities in the US, it is usually possible to find public information about the salary of people at your rank in the department you’re applying to. Don’t take these numbers as gospel — they may be slightly out of date and sometimes don’t include all forms of pay — but they can be quite helpful. Otherwise, you are unlikely to have a great idea of the potential salary range for your position.

Needless to say, negotiations should be undertaken with lots of advice from trusted faculty mentors. When you get the offer, express your appreciation and tell the caller that you will need some time to consider it. At this point, take some time to celebrate or do whatever else you’d like and once the dust settles, it’s time to do some homework. You should assume that you have at least a week to respond, but often there is more time and this will be communicated. If you aren’t given a timeline, assume it’s more than a week but it would be a good idea to check in before too much time passes.

From the other institution’s perspective, there are likely very few people who could potentially get this job by the time they have offered you. It is often not possible to “re-open” the search so it is probably down to you and whichever other finalists who were deemed acceptable and haven’t already been offered. That means you might be the only option left.

Most hiring units really don’t want to end up with nobody hired because there is a risk that their dean does not allow them to try to hire for it again next year. That’s not to mention that sometimes these positions are meant to fill immediate, pressing needs. In other words, you probably have some leverage although precisely how much is hard to know. This is true even if you have no other offers and don’t believe you’ll be getting any more offers.

As a general rule, you need to figure out what kind of resources the institution has available. A school that is clearly low on funds will not have much, if any, room to negotiate on most of these things. This is where your adviser will really be able to help figuring out what to do.

Links:

- Guide from Chris Blatt

- Advice from The Professor is In

- Advice from John Champaign

- Information from U Colorado career services

- Negotiation slide deck from APA (psychology) [PDF]

- Twitter thread from Hakeem Jefferson (political scientist)

- Community spreadsheet of political science pay and startup packages

Links with general/wide-ranging advice

These are some links that don’t fit neatly into the above categories. They are all focusing on other disciplines or no discipline in particular.

- Dan Korman’s philosophy job market guide

- Stacy Branham’s application materials (human-computer interaction)

- Q&A on campus visit behavior

- Science principles for the job market

- Chris Blattman’s overall job market advice

- Statistics about the path to becoming a professor in psychology

Just a note about that last link since it could give a form of sticker shock: publication expectations in psychology are much higher than communication, in my experience, so don’t be too surprised by the number of publications by the average hire if you’re a communication student/job candidate.